Zimbabwe - Customary law – Consumption use

CONSUMPTION USE

Customary norms and practices

Zimbabwe

BACKGROUND

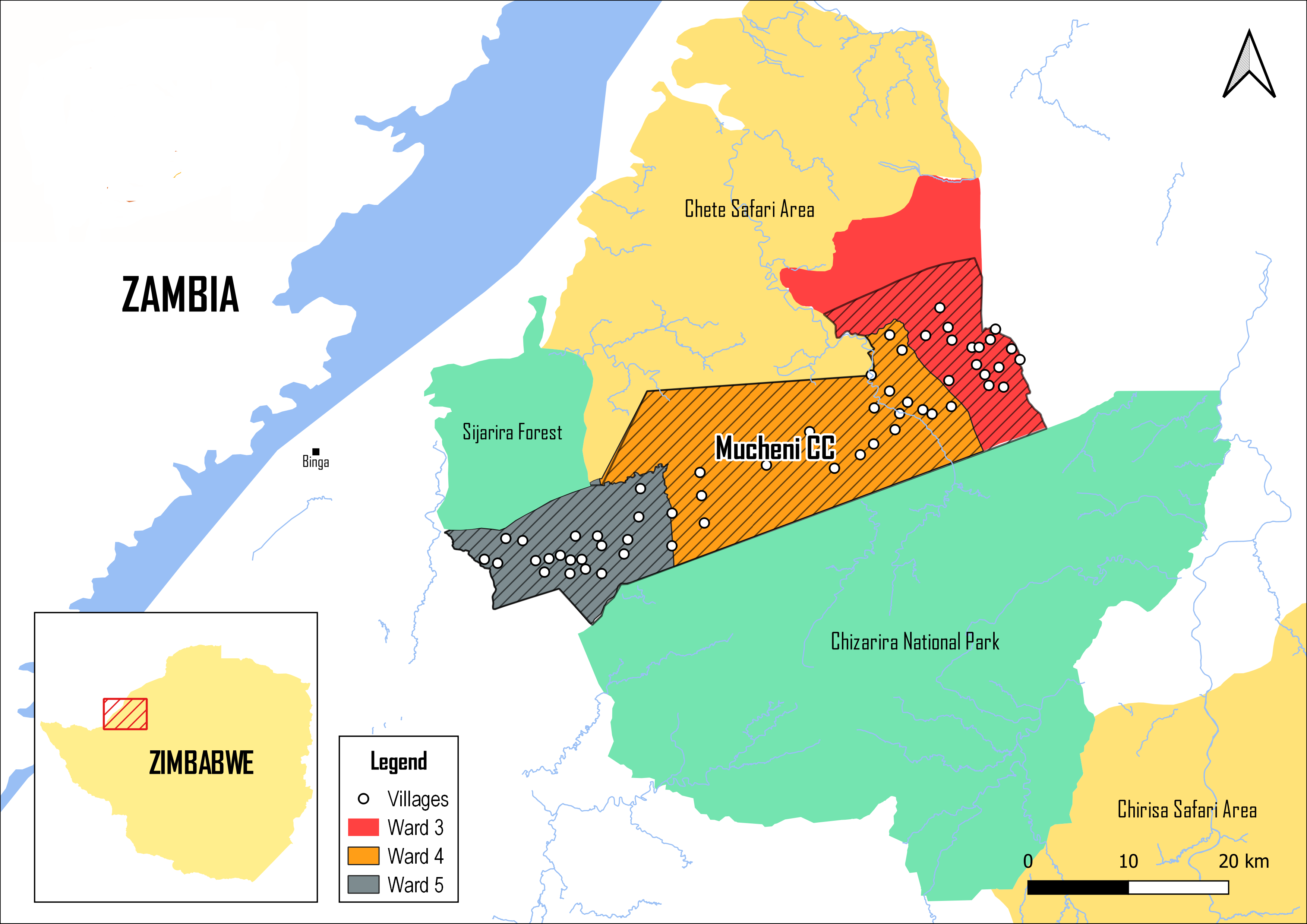

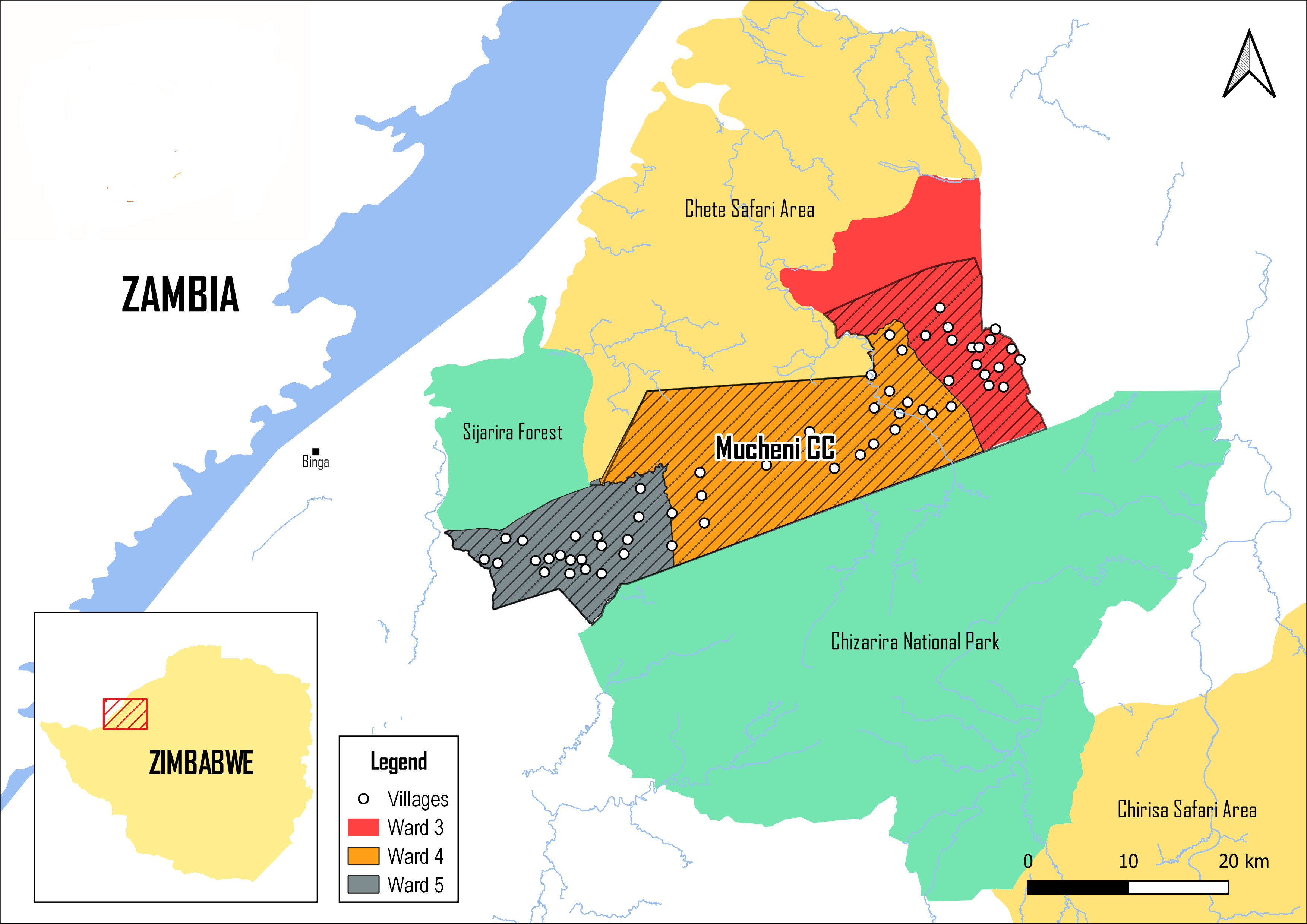

Binga District, situated in the Zambezi Valley, is mainly inhabited by the Tonga and Ndebele. The Tonga are the majority inhabitants of the area and regard the Ndebele as newcomers. Tonga people identify strongly with the Zambezi River, this being the centre of their economic, social, religious, cultural and environmental livelihoods.

In the pre-colonial period, until 1888, the Tonga were a stateless society, known for having no paramount chief and historically were a matrilineal society.

The colonial administration by introducing chiefs and headmen disrupted Tonga's age-old egalitarianism and led to the solidification of fixed boundaries across and between villages as well as the introduction of new ways of dealing with criminal cases that were centred around the chief’s court.

The construction of the Kariba Dam along the Zambezi River, with the related forced relocation in land of small size and poor quality, significantly impacted the lives and livelihoods of the Tonga who were directly and heavily reliant upon the Zambezi River landscape. Indeed, the colonial government established fishing camps far away from resettlement areas, and only men were allowed at these fishing camps. At the same time traditional and cultural wildlife management systems were abrogated and criminalized by introducing the need of hunting permits.

Even with political independence in 1980 the Tonga continued being marginalized, without rights to manage and benefit from wildlife resources in the safaris and national game parks abutting their new villages. The attempt to extend these rights to the local communities by granting the right to use wildlife in communal areas to Rural District Councils (RDCs), has in fact led to tensions between communities and RDCs on revenue-sharing arrangements.

The 2013 Constitution expressly recognizes customary law and customary institutions. It recognizes the role of traditional leaders in resolving disputes among people in their communities in accordance with customary law. It also establishes a dual court structure, recognizing customary law courts whose jurisdiction consists primarily in the application of customary law.

Besides the Constitution, there are several statutes which recognize customary law. These include the Customary Law and Local Courts Act (CLLCA), the Traditional Leaders Act, the Communal Land Act, and the Environmental Management (Access to Genetic Resources and Indigenous Genetic Resource-based Knowledge) Regulations, 2009. All law, customary and statutory , is subject to compliance with the Constitution of Zimbabwe. Any law inconsistent with it is invalid to the extent of the inconsistency.

According to the CLLCA, customary law is still applied in civil matters where the parties have agreed. Local courts are presided over by chiefs and have jurisdiction over any civil case in which customary law is applicable. However, their jurisdiction is excluded, among others, where the claim is not determinable by customary law; or where the claim or the value of any article claimed exceeds a certain amount; or also to determine rights in respect of land or other immovable property.

The Traditional Leaders Act governs the structure of traditional leadership and its duties, which include the resolution of disputes and management of natural resources. Furthermore, traditional leaders have to be consulted in the allocation of communal land under the Communal Land Act. However, customary law’s application is not always recognized in sectoral legislation, particularly in the management of wildlife. Indeed, while the Environmental Management (Access to Genetic Resources and Indigenous Genetic Resource-based Knowledge) Regulations, 2009, provide for community rights over genetic resources, including animal genetic material, the Parks and Wildlife Act (PWA) does not expressly mention any form of customary hunting that traditionally occurred for both subsistence and cultural purposes.

CONSUMPTION USE

Customary practices for the use of terrestrial wildlife

Historically, the Tonga used the following types of hunting methods: simple noose (wire/fibre) for small game and birds, trapping (spring pole snares for big game), big game pits for leopards and other predators, traditional guns (muzzle-loading guns) for a variety of game, use of dogs for smaller antelopes, spear hunting (the main form of hunting), elephant spearing, hippopotamus harpooning, and fire drives for big game. The Tonga also used poison on the spear, particularly for big game.

For fishing, the Tonga used spears, mazubo (traditional hand-woven reed baskets) and poison. Some forms of traditional fishing methods, like the use of rod and line, are also currently recognized as fishing methods by the PWA Regulations.

Although the Environmental Management (Access to Genetic Resources and Indigenous Genetic Resource-based Knowledge) Regulations, 2009, recognizes access to and benefit from genetic resources, which include animal genetic material, the Parks and Wildlife Act does not expressly mention any form of hunting for either subsistence or cultural purposes, which therefore results in the non-regulation of relevant methods and tools. However, in recent consultations, in the review of Zimbabwe’s wildlife policy, communities in the project area alluded to the fact that they are involved in hunting activities as a source of bushmeat. Similarly, Tonga people living near the river try to make a living from small-scale fishing, as they cannot afford the recommended fishing rigs and nets, and government fishing licences are beyond their financial reach.

Taboos related to hunting and the consumption of wild meat

The Tonga have used taboos as an effective measure in the management of their natural resources and surroundings for millennia. Taboos may be specific to areas, to wildlife species or to consumer categories. Among the first, areas such as shrine forests, hot springs and sacred pools could not be used for any purpose other than those specified by traditional chiefs and village spirit mediums. Shrines and other sacred places in the landscape where a spirit is believed to dwell can only be approached with caution. Trees, grass and animals in such places could not be exploited or harvested. It is taboo even to cut down trees for firewood.

Concerning wildlife species, indiscriminate killing of animals and birds is not allowed by custom. Further, killing and eating certain species which have someone’s totem is considered a taboo. Some of the common wildlife species associated with totems include the warthog, eland, anteater, pangolin, baboon, crocodile, monkey, lion, hyena and the fish Clarias gariepinus (muramba). Hunting, trapping, killing or eating a clan totem is not allowed, as such animals are perceived as sacred. The belief is that the vitality and survival of the clan are dependent on the abundance of clan animals. Beside clans’ specific totems, birds such as tumba (owls) are regarded as “birds of bad omen” and should not be killed, and the same applies to the killing of scavenger birds as they are thought to clean the environment. Killing fish eagles is also taboo as they direct people to where tigerfish can be found. Moreover, some birds are deemed to be kingly; among such birds is one locally called nduba, a colourful and rare bird preserved for chiefs who sparingly use its feathers to decorate their regalia.

The Tonga hunters were expected to give certain parts of captured animals as a customary tribute to the chief. These parts included the following: the side of a medium-sized animal (e.g. kudu, buffalo) that hit the ground after the animal was killed, pangolin, elephant trunk and elephant tusks, a living scaly anteater (inkakha), the skin and claws of a lion, and leopard. The pangolin and the elephant trunk were considered special meat for the chief. No one else was allowed to eat the pangolin. The chief shared his tribute with the community, particularly those who came from families that do not have hunters, the elderly and the sick. The bushmeat was not sold and there were no barter arrangements. Individual hunters divided their catch among specific relatives and those who helped them in hunting. However, besides clan’s totems, specific taboos on consumers’ categories also apply. Pregnant women cannot eat eggs or the meat of eland, elephant, warthog and zebra. It is believed that if they eat eggs the child to be born would delay growing hair. Eating elephant meat would cause the child to grow slowly. Zebra meat would cause the child to be marked like a Zebra. Eland meat would cause the child to be vulnerable. Children are not allowed to eat eggs, rats, guinea fowl or muramba (Clarias gariepinus). Muramba can cause marriages to fail and water springs to dry up. The rat affects fertility.

It is believed that failure to observe and comply with the taboos among the Tonga will anger the spirits of the ancestors who may decide to punish the culprit with bad luck, loss of teeth or even death for those who eat clan meat. The punishment can also affect the culprit’s family. The community may also be affected since the failure to observe the taboos can result in the drying up of pools, and forests failing to bear wild fruits for both animals and human beings.