Guyana- Customary law - Consumption use

CONSUMPTION USE

Customary norms and practices

Guyana

BACKGROUND

The Constitution of the Cooperative Republic of Guyana provides special rights and representation organs for Amerindians. While customary law is not expressly recognized, the Constitution recognizes the right of indigenous people to the protection, preservation and promulgation of their languages, cultural heritage and way of life. It also establishes, for the purpose of strengthening social justice and the rule of law, the Indigenous Peoples’ Commission, whose functions include, among others, the promotion and protection of indigenous people’s rights and the empowerment of Amerindian authorities.

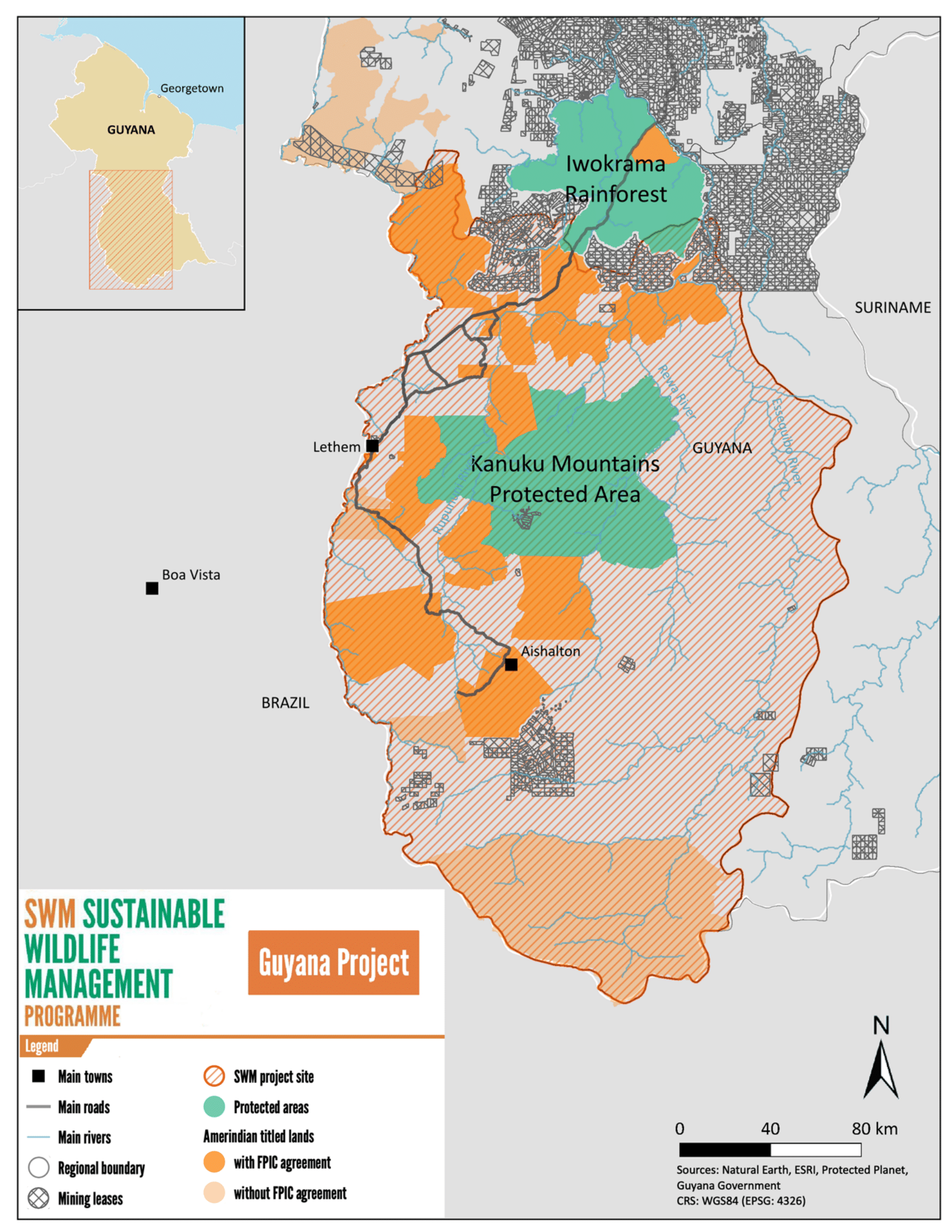

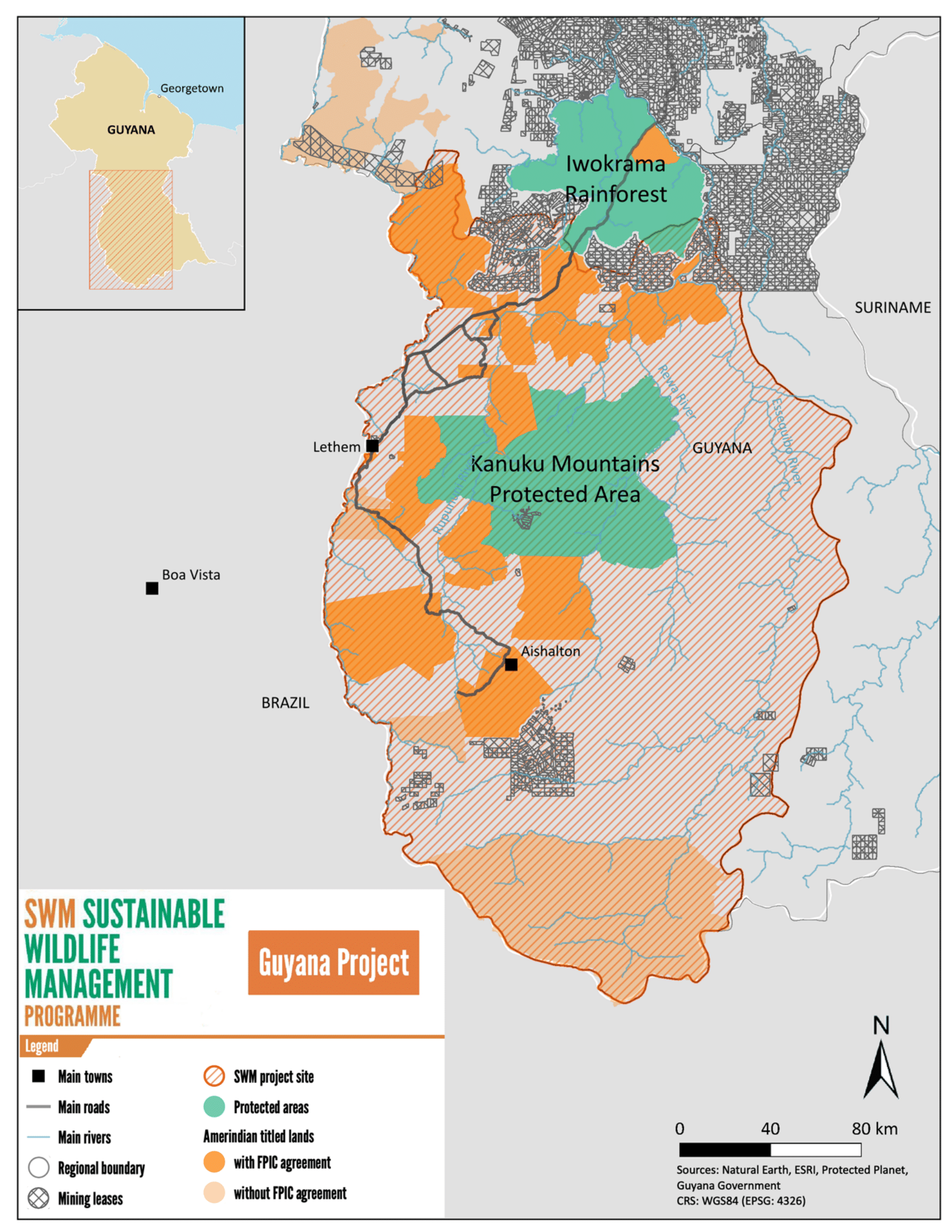

Similarly, the Amerindian Act of 2006 does not explicitly recognize customary law, but it establishes traditional rights for Amerindians understood as subsistence rights or privileges. It also establishes a land demarcation and titling process to grant formal land rights over lands traditionally occupied by Amerindians and formally recognizes Amerindian authorities and representation bodies. The Act gives powers to Village Councils to administer village lands (lands under a land title) and to make rules governing different aspects such as access and occupation of lands and use of natural resources including wildlife and fisheries. Such rules are subject to prior approval by the Minister of Amerindian Affairs and publication in the Official Gazette. Unlike Village Councils, Amerindian communities do not hold similar powers as they do not hold formal land titles.The Rupununi (Region 9) is in the southwest of the country and covers 57 750 km2 with approximately 24000 inhabitants who are mostly indigenous peoples: Wai-Wai in the forested deep south, Wapichan in South and South Central, and Makushi in the North. This section focuses in particular on the Wapichan, whose livelihoods are based on fishing, hunting, rearing domestic livestock and the cultivation of fruit trees.

The Wapichan traditional territory (wiizi) lies in the South Rupununi between the Takutu, Kassikaiytu and Essequibo rivers. The Wapichan wiizi represents an extension of the Rio Branco savannahs in Brazil, and is therefore distinct from other parts of Guyana. It harbours a highly diverse habitat with continuous tracts of primary forest, ‘bush islands’, gallery forests, open and tree savannah, and seasonally flooded wetlands. It is home to many iconic Amazonian species of fish and wildlife, some of which are rare or threatened globally, like the red siskin (Spinus cuculatus), giant anteater (Myrmecophaga tridactyla), yellow-spotted river turtle (Podocnemis unifilis) and black curassow (Crax alector).

In the Wapichan Wiizi, there are 13 main villages and nine smaller satellite communities who are represented in the South Rupununi District Council (SRDC), which is their representative body. Wapichan settlements are spread over a wide area of savannah-forest ecotone. Their modern language is Wapichan which belongs to the Arawak family, but most people have knowledge of English as they attend government primary schools. Portuguese is also widely known due to the proximity with Brazil. The Wapichan Territorial Management Plan developed by the SRDC is based on customary rules and is recognized by Statutory Law.

CONSUMPTION USE

Customary practices for the use of terrestrial wildlife

Hunting is traditionally carried out by the Wapichan people using bows and arrows and a variety of traps, although guns are also available in most villages. The use of guns is limited due to strict customary regulations on gun ownership and the high cost of cartridges. Most hunters also own hunting dogs that are used to retrieve game. Ancient trapping techniques are still used today, such as the method of “beating up” game towards waiting “marksmen” who stand at agreed waiting points with a bow or shotgun. Trapping is used for some species, such as the collared peccary. Another customary hunting method involves the construction of an elevated platform, “the Wabani,” at sites where game animals are known to feed and drink, including fruit-bearing trees, pools and saltlicks in the bush. Platforms are also used to shoot game feeding on crops or bush-fallows. The use of fire is also common in hunting and fishing practices. Hunting grounds are located throughout the Wapichan territory in mountains, bush mouths (forest-savannah edge), deep bush, bush islands, savannah and along creek margins, and are shared by all Wapichan communities. The jurisdiction over these areas is shared between adjacent communities and overseen by traditional authorities (Toshaos). Once or twice a year in December and April, a larger group of hunters engage in a community hunt over approximately two weeks.

Taboos related to hunting and the consumption of wild meat

Under Wapichan customary law, people cannot kill animals considered ‘decorative’ (animals that “decorate” land and make it more beautiful), such as the giant anteater and tamarin monkeys (Saguinus midas). Some animals are believed to have supernatural high levels of spiritual powers, such as Anacondas (Eunectes murinus) and Boa (Constrictor constrictor). Similarly, people should not kill water eels or stingrays because this might scare the fish. Anyone killing these species is subject to the revenge of their spirits and thus are avoided. Customary rules also indicate that pregnant wildlife and young animals as well as the leader of the White-Lipped Peccary (Tayassu pecari) herd should not be hunted.

Some people avoid the consumption of species such as tapir (Tapirus terrestris), grey-brocket deer (Mazama nemorivaga), tortoises (Chelonoidis spp.), capybara (Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris), and white-lipped peccary (Tayassu pecari) for health and cultural reasons. However, these taboos are not generalized, and most people continue to consume these species. Young women may only eat certain fish and meat when they take part in traditional puberty rites. The shaman is a special figure that provides advice on the avoidance of certain meats or fish and remedies to people experiencing negative consequences because of the breach of taboos.

Menstruating women should avoid forest areas, rivers, creeks, lakes, and springs. They are considered to be particularly vulnerable to the attacks of boa (Constrictor constrictor) spirits during menstruation. Many taboos, particularly those relating to fish or meat consumption, are associated with pregnant women or women during their menstrual cycle. There are also taboos related to areas in which hunting and fishing restrictions apply. Some areas are considered sacred and are off-limits or require special rituals to be accessed as they are inhabited by animal spirits. Taboos related to wildmeat consumption may also serve as a management tool for natural resources. This is more evident for some species such as the lowland tapir (Tapirus terrestris), which has a low reproduction rate.